|

george orwell

1984

- NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR

- prima pubblicazione 8 giugno 1949

. 2021 serie tv

-

https://tg24.sky.it/2021/01/13/orwell-1984-serie-tv

Every record has been destroyed or falsified, every book has

been rewritten, every picture has been repainted, every statue

and street and building has been renamed, every date has been

altered . And that process is continuing day by day and minute by

minute . History has stopped .

...

Thoughtcrime does not entail death

thoughtcrime IS

death

banned and challenged YA books

.

The Bluest Eye - Toni

Morrison

. The Kite Runner - Khaled

Hosseini

. The House on Mango Street -

Sandra Cisneros

. 1984 -

george orwell

latimes.com - 2015

If the Party could thrust its hand into the past and say of this or that

event, it never happened - that, surely, was more terrifying than mere

torture and death ?

.

Tragedy, he perceived, belonged to the ancient time, to a time when there

was still privacy, love, and friendship, and when the members of a family

stood by one another without needing to know the reason .

chap

3

.

The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness and

for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better .

.

Part One

Chapter 1

It was a bright cold day in April,

and the clocks were striking thirteen.

Winston Smith, his chin nuzzled into

his breast in an effort to escape the vile wind, slipped quickly through the

glass doors of Victory Mansions, though not quickly enough to prevent a swirl

of gritty dust from entering along with him.

The hallway smelt of boiled cabbage and old rag mats. At one end of it a

coloured poster, too large for indoor display, had been tacked to the wall. It

depicted simply an enormous face, more than a metre wide: the face of a man of

about forty-five, with a heavy black moustache and ruggedly handsome features.

Winston made for the stairs. It was no use trying the lift. Even at the best

of times it was seldom working, and at present the electric current was cut

off during daylight hours. It was part of the economy drive in preparation for

Hate Week. The flat was seven flights up, and Winston, who was thirty-nine and

had a varicose ulcer above his right ankle, went slowly, resting several times

on the way. On each landing, opposite the lift-shaft, the poster with the

enormous face gazed from the wall. It was one of those pictures which are so

contrived that the eyes follow you about when you move.

BIG BROTHER IS

WATCHING YOU

the caption beneath it ran.

Inside the flat a fruity voice was reading out a list of figures which had

something to do with the production of pig-iron. The voice came from an oblong

metal plaque like a dulled mirror which formed part of the surface of the

right-hand wall. Winston turned a switch and the voice sank somewhat, though

the words were still distinguishable. The instrument (the telescreen, it was

called) could be dimmed, but there was no way of shutting it off completely.

He moved over to the window: a smallish, frail figure, the meagreness of his

body merely emphasized by the blue overalls which were the uniform of the

party. His hair was very fair, his face naturally sanguine, his skin roughened

by coarse soap and blunt razor blades and the cold of the winter that had just

ended.

Outside, even through the shut window-pane, the world looked cold. Down in the

street little eddies of wind were whirling dust and torn paper into spirals,

and though the sun was shining and the sky a harsh blue, there seemed to be no

colour in anything, except the posters that were plastered everywhere. The

blackmoustachio'd face gazed down from every commanding corner. There was one

on the house-front immediately opposite.

BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU, the caption said, while the dark eyes looked deep into Winston's own. Down at

streetlevel another poster, torn at one corner, flapped fitfully in the wind,

alternately covering and uncovering the single word

INGSOC. In the far

distance a helicopter skimmed down between the roofs, hovered for an instant

like a bluebottle, and darted away again with a curving flight. It was the

police patrol, snooping into people's windows. The patrols did not matter,

however. Only the Thought Police mattered.

Behind Winston's back the voice from the telescreen was still babbling away

about pig-iron and the overfulfilment of the Ninth Three-Year Plan. The

telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously. Any sound that Winston

made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up by it,

moreover, so long as he remained within the field of vision which the metal

plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as heard. There was of course no

way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often,

or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was

guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time.

But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had

to live -- did live, from habit that became instinct -- in the assumption that

every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement

scrutinized.

Winston kept his back turned to the telescreen. It was safer, though, as he

well knew, even a back can be revealing. A kilometre away the Ministry of

Truth, his place of work, towered vast and white above the grimy landscape.

This, he thought with a sort of vague distaste -- this was London, chief city

of Airstrip One, itself the third most populous of the provinces of Oceania.

He tried to squeeze out some childhood memory that should tell him whether

London had always been quite like this. Were there always these vistas of

rotting nineteenth-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber,

their windows patched with cardboard and their roofs with corrugated iron,

their crazy garden walls sagging in all directions? And the bombed sites where

the plaster dust swirled in the air and the willow-herb straggled over the

heaps of rubble; and the places where the bombs had cleared a larger patch and

there had sprung up sordid colonies of wooden dwellings like chicken-houses?

But it was no use, he could not remember: nothing remained of his childhood

except a series of bright-lit tableaux occurring against no background and

mostly unintelligible.

The Ministry of Truth -- Minitrue, in Newspeak -- was startlingly different

from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of

glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, 300 metres into

the air. From where Winston stood it was just possible to read, picked out on

its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

LA GUERRA E' PACE - LA LIBERTA' E' SCHIAVITU' - L'IGNORANZA E'

FORZA

The Ministry of Truth contained,

it was said, three thousand rooms above ground level, and corresponding

ramifications below. Scattered about London there were just three other

buildings of similar appearance and size. So completely did they dwarf the

surrounding architecture that from the roof of Victory Mansions you could see

all four of them simultaneously. They were the homes of the four Ministries

between which the entire apparatus of government was divided. The Ministry of

Truth, which concerned itself with news, entertainment, education, and the

fine arts. The Ministry of Peace, which concerned itself with war. The

Ministry of Love, which maintained law and order. And the Ministry of Plenty,

which was responsible for economic affairs. Their names, in Newspeak: Minitrue,

Minipax, Miniluv, and Miniplenty.

The Ministry of Love was the really frightening one. There were no windows in

it at all. Winston had never been inside the Ministry of Love, nor within half

a kilometre of it. It was a place impossible to enter except on official

business, and then only by penetrating through a maze of barbed-wire

entanglements, steel doors, and hidden machine-gun nests. Even the streets

leading up to its outer barriers were roamed by gorilla-faced guards in black

uniforms, armed with jointed truncheons.

Winston turned round abruptly. He had set his features into the expression of

quiet optimism which it was advisable to wear when facing the telescreen. He

crossed the room into the tiny kitchen. By leaving the Ministry at this time

of day he had sacrificed his lunch in the canteen, and he was aware that there

was no food in the kitchen except a hunk of dark-coloured bread which had got

to be saved for tomorrow's breakfast. He took down from the shelf a bottle of

colourless liquid with a plain white label marked

VICTORY GIN. It gave off a

sickly, oily smell, as of Chinese ricespirit. Winston poured out nearly a

teacupful, nerved himself for a shock, and gulped it down like a dose of

medicine.

Instantly his face turned scarlet and the water ran out of his eyes. The stuff

was like nitric acid, and moreover, in swallowing it one had the sensation of

being hit on the back of the head with a rubber club. The next moment, however,

the burning in his belly died down and the world began to look more cheerful.

He took a cigarette from a crumpled packet marked

VICTORY CIGARETTES and

incautiously held it upright, whereupon the tobacco fell out on to the floor.

With the next he was more successful. He went back to the living-room and sat

down at a small table that stood to the left of the telescreen. From the table

drawer he took out a penholder, a bottle of ink, and a thick, quarto-sized

blank book with a red back and a marbled cover.

For some reason the telescreen in the living-room was in an unusual position.

Instead of being placed, as was normal, in the end wall, where it could

command the whole room, it was in the longer wall, opposite the window. To one

side of it there was a shallow alcove in which Winston was now sitting, and

which, when the flats were built, had probably been intended to hold

bookshelves. By sitting in the alcove, and keeping well back, Winston was able

to remain outside the range of the telescreen, so far as sight went. He could

be heard, of course, but so long as he stayed in his present position he could

not be seen. It was partly the unusual geography of the room that had

suggested to him the thing that he was now about to do.

But it had also been suggested by the book that he had just taken out of the

drawer. It was a peculiarly beautiful book. Its smooth creamy paper, a little

yellowed by age, was of a kind that had not been manufactured for at least

forty years past. He could guess, however, that the book was much older than

that. He had seen it lying in the window of a frowsy little junk-shop in a

slummy quarter of the town (just what quarter he did not now remember) and had

been stricken immediately by an overwhelming desire to possess it. Party

members were supposed not to go into ordinary shops ('dealing on the free

market', it was called), but the rule was not strictly kept, because there

were various things, such as shoelaces and razor blades, which it was

impossible to get hold of in any other way. He had given a quick glance up and

down the street and then had slipped inside and bought the book for two

dollars fifty. At the time he was not conscious of wanting it for any

particular purpose. He had carried it guiltily home in his briefcase. Even

with nothing written in it, it was a compromising possession.

The thing that he was about to do was to open a diary. This was not illegal (nothing

was illegal, since there were no longer any laws), but if detected it was

reasonably certain that it would be punished by death, or at least by

twenty-five years in a forced-labour camp. Winston fitted a nib into the

penholder and sucked it to get the grease off. The pen was an archaic

instrument, seldom used even for signatures, and he had procured one,

furtively and with some difficulty, simply because of a feeling that the

beautiful creamy paper deserved to be written on with a real nib instead of

being scratched with an ink-pencil. Actually he was not used to writing by

hand. Apart from very short notes, it was usual to dictate everything into the

speakwrite which was of course impossible for his present purpose. He dipped

the pen into the ink and then faltered for just a second. A tremor had gone

through his bowels. To mark the paper was the decisive act. In small clumsy

letters he wrote:

April 4th, 1984.

He sat back. A sense of complete

helplessness had descended upon him. To begin with, he did not know with any

certainty that this was 1984. It must be round about that date, since

he was fairly sure that his age was thirty-nine, and he believed that he had

been born in 1944 or 1945; but it was never possible nowadays to pin down any

date within a year or two.

For whom, it suddenly occurred to him to wonder, was he writing this diary?

For the future, for the unborn. His mind hovered for a moment round the

doubtful date on the page, and then fetched up with a bump against the

Newspeak word doublethink. For the first time the magnitude of what he

had undertaken came home to him. How could you communicate with the future? It

was of its nature impossible. Either the future would resemble the present, in

which case it would not listen to him: or it would be different from it, and

his predicament would be meaningless.

For some time he sat gazing stupidly at the paper. The telescreen had changed

over to strident military music. It was curious that he seemed not merely to

have lost the power of expressing himself, but even to have forgotten what it

was that he had originally intended to say. For weeks past he had been making

ready for this moment, and it had never crossed his mind that anything would

be needed except courage. The actual writing would be easy. All he had to do

was to transfer to paper the interminable restless monologue that had been

running inside his head, literally for years. At this moment, however, even

the monologue had dried up. Moreover his varicose ulcer had begun itching

unbearably. He dared not scratch it, because if he did so it always became

inflamed. The seconds were ticking by. He was conscious of nothing except the

blankness of the page in front of him, the itching of the skin above his ankle,

the blaring of the music, and a slight booziness caused by the gin.

Suddenly he began writing in sheer panic, only imperfectly aware of what he

was setting down. His small but childish handwriting straggled up and down the

page, shedding first its capital letters and finally even its full stops:

April 4th, 1984. Last night to

the flicks. All war films. One very good one of a ship full of refugees

being bombed somewhere in the Mediterranean. Audience much amused by shots

of a great huge fat man trying to swim away with a helicopter after him,

first you saw him wallowing along in the water like a porpoise, then you saw

him through the helicopters gunsights, then he was full of holes and the sea

round him turned pink and he sank as suddenly as though the holes had let in

the water, audience shouting with laughter when he sank. then you saw a

lifeboat full of children with a helicopter hovering over it. there was a

middle-aged woman might have been a jewess sitting up in the bow with a

little boy about three years old in her arms. little boy screaming with

fright and hiding his head between her breasts as if he was trying to burrow

right into her and the woman putting her arms round him and comforting him

although she was blue with fright herself, all the time covering him up as

much as possible as if she thought her arms could keep the bullets off him.

then the helicopter planted a 20 kilo bomb in among them terrific flash and

the boat went all to matchwood. then there was a wonderful shot of a child's

arm going up up up right up into the air a helicopter with a camera in its

nose must have followed it up and there was a lot of applause from the party

seats but a woman down in the prole part of the house suddenly started

kicking up a fuss and shouting they didnt oughter of showed it not in front

of kids they didnt it aint right not in front of kids it aint until the

police turned her turned her out i dont suppose anything happened to her

nobody cares what the proles say typical prole reaction they never --

Winston stopped writing, partly

because he was suffering from cramp. He did not know what had made him pour

out this stream of rubbish. But the curious thing was that while he was doing

so a totally different memory had clarified itself in his mind, to the point

where he almost felt equal to writing it down. It was, he now realized,

because of this other incident that he had suddenly decided to come home and

begin the diary today.

It had happened that morning at the Ministry, if anything so nebulous could be

said to happen.

It was nearly eleven hundred, and in the Records Department, where Winston

worked, they were dragging the chairs out of the cubicles and grouping them in

the centre of the hall opposite the big telescreen, in preparation for the Two

Minutes Hate. Winston was just taking his place in one of the middle rows when

two people whom he knew by sight, but had never spoken to, came unexpectedly

into the room. One of them was a girl whom he often passed in the corridors.

He did not know her name, but he knew that she worked in the Fiction

Department. Presumably -- since he had sometimes seen her with oily hands and

carrying a spanner she had some mechanical job on one of the novel-writing

machines. She was a bold-looking girl, of about twenty-seven, with thick hair,

a freckled face, and swift, athletic movements. A narrow scarlet sash, emblem

of the Junior Anti-Sex League, was wound several times round the waist of her

overalls, just tightly enough to bring out the shapeliness of her hips.

Winston had disliked her from the very first moment of seeing her. He knew the

reason. It was because of the atmosphere of hockey-fields and cold baths and

community hikes and general clean-mindedness which she managed to carry about

with her. He disliked nearly all women, and especially the young and pretty

ones. It was always the women, and above all the young ones, who were the most

bigoted adherents of the Party, the swallowers of slogans, the amateur spies

and nosers-out of unorthodoxy. But this particular girl gave him the

impression of being more dangerous than most. Once when they passed in the

corridor she gave him a quick sidelong glance which seemed to pierce right

into him and for a moment had filled him with black terror. The idea had even

crossed his mind that she might be an agent of the Thought Police. That, it

was true, was very unlikely. Still, he continued to feel a peculiar uneasiness,

which had fear mixed up in it as well as hostility, whenever she was anywhere

near him.

The other person was a man named O'Brien, a member of the Inner Party and

holder of some post so important and remote that Winston had only a dim idea

of its nature. A momentary hush passed over the group of people round the

chairs as they saw the black overalls of an Inner Party member approaching. O'Brien

was a large, burly man with a thick neck and a coarse, humorous, brutal face.

In spite of his formidable appearance he had a certain charm of manner. He had

a trick of resettling his spectacles on his nose which was curiously disarming

-- in some indefinable way, curiously civilized. It was a gesture which, if

anyone had still thought in such terms, might have recalled an

eighteenth-century nobleman offering his snuffbox. Winston had seen O'Brien

perhaps a dozen times in almost as many years. He felt deeply drawn to him,

and not solely because he was intrigued by the contrast between O'Brien's

urbane manner and his prize-fighter's physique. Much more it was because of a

secretly held belief -- or perhaps not even a belief, merely a hope -- that O'Brien's

political orthodoxy was not perfect. Something in his face suggested it

irresistibly. And again, perhaps it was not even unorthodoxy that was written

in his face, but simply intelligence. But at any rate he had the appearance of

being a person that you could talk to if somehow you could cheat the

telescreen and get him alone. Winston had never made the smallest effort to

verify this guess: indeed, there was no way of doing so. At this moment O'Brien

glanced at his wrist-watch, saw that it was nearly eleven hundred, and

evidently decided to stay in the Records Department until the Two Minutes Hate

was over. He took a chair in the same row as Winston, a couple of places away.

A small, sandy-haired woman who worked in the next cubicle to Winston was

between them. The girl with dark hair was sitting immediately behind.

The next moment a hideous, grinding speech, as of some monstrous machine

running without oil, burst from the big telescreen at the end of the room. It

was a noise that set one's teeth on edge and bristled the hair at the back of

one's neck. The Hate had started.

As usual, the face of Emmanuel Goldstein, the Enemy of the People, had flashed

on to the screen. There were hisses here and there among the audience. The

little sandy-haired woman gave a squeak of mingled fear and disgust. Goldstein

was the renegade and backslider who once, long ago (how long ago, nobody quite

remembered), had been one of the leading figures of the Party, almost on a

level with Big Brother himself, and then had engaged in counter-revolutionary

activities, had been condemned to death, and had mysteriously escaped and

disappeared. The programmes of the Two Minutes Hate varied from day to day,

but there was none in which Goldstein was not the principal figure. He was the

primal traitor, the earliest defiler of the Party's purity. All subsequent

crimes against the Party, all treacheries, acts of sabotage, heresies,

deviations, sprang directly out of his teaching. Somewhere or other he was

still alive and hatching his conspiracies: perhaps somewhere beyond the sea,

under the protection of his foreign paymasters, perhaps even -- so it was

occasionally rumoured -- in some hiding-place in Oceania itself.

Winston's diaphragm was constricted. He could never see the face of Goldstein

without a painful mixture of emotions. It was a lean Jewish face, with a great

fuzzy aureole of white hair and a small goatee beard -- a clever face, and yet

somehow inherently despicable, with a kind of senile silliness in the long

thin nose, near the end of which a pair of spectacles was perched. It

resembled the face of a sheep, and the voice, too, had a sheep-like quality.

Goldstein was delivering his usual venomous attack upon the doctrines of the

Party -- an attack so exaggerated and perverse that a child should have been

able to see through it, and yet just plausible enough to fill one with an

alarmed feeling that other people, less level-headed than oneself, might be

taken in by it. He was abusing Big Brother, he was denouncing the dictatorship

of the Party, he was demanding the immediate conclusion of peace with Eurasia,

he was advocating freedom of speech, freedom of the Press, freedom of assembly,

freedom of thought, he was crying hysterically that the revolution had been

betrayed -- and all this in rapid polysyllabic speech which was a sort of

parody of the habitual style of the orators of the Party, and even contained

Newspeak words: more Newspeak words, indeed, than any Party member would

normally use in real life. And all the while, lest one should be in any doubt

as to the reality which Goldstein's specious claptrap covered, behind his head

on the telescreen there marched the endless columns of the Eurasian army --

row after row of solid-looking men with expressionless Asiatic faces, who swam

up to the surface of the screen and vanished, to be replaced by others exactly

similar. The dull rhythmic tramp of the soldiers' boots formed the background

to Goldstein's bleating voice.

Before the Hate had proceeded for thirty seconds, uncontrollable exclamations

of rage were breaking out from half the people in the room. The self-satisfied

sheep-like face on the screen, and the terrifying power of the Eurasian army

behind it, were too much to be borne: besides, the sight or even the thought

of Goldstein produced fear and anger automatically. He was an object of hatred

more constant than either Eurasia or Eastasia, since when Oceania was at war

with one of these Powers it was generally at peace with the other. But what

was strange was that although Goldstein was hated and despised by everybody,

although every day and a thousand times a day, on platforms, on the telescreen,

in newspapers, in books, his theories were refuted, smashed, ridiculed, held

up to the general gaze for the pitiful rubbish that they were in spite of all

this, his influence never seemed to grow less. Always there were fresh dupes

waiting to be seduced by him. A day never passed when spies and saboteurs

acting under his directions were not unmasked by the Thought Police. He was

the commander of a vast shadowy army, an underground network of conspirators

dedicated to the overthrow of the State. The Brotherhood, its name was

supposed to be. There were also whispered stories of a terrible book, a

compendium of all the heresies, of which Goldstein was the author and which

circulated clandestinely here and there. It was a book without a title. People

referred to it, if at all, simply as the book. But one knew of such

things only through vague rumours. Neither the Brotherhood nor the book

was a subject that any ordinary Party member would mention if there was a way

of avoiding it.

In its second minute the Hate rose to a frenzy. People were leaping up and

down in their places and shouting at the tops of their voices in an effort to

drown the maddening bleating voice that came from the screen. The little

sandy-haired woman had turned bright pink, and her mouth was opening and

shutting like that of a landed fish. Even O'Brien's heavy face was flushed. He

was sitting very straight in his chair, his powerful chest swelling and

quivering as though he were standing up to the assault of a wave. The

dark-haired girl behind Winston had begun crying out 'Swine! Swine! Swine!'

and suddenly she picked up a heavy Newspeak dictionary and flung it at the

screen. It struck Goldstein's nose and bounced off; the voice continued

inexorably. In a lucid moment Winston found that he was shouting with the

others and kicking his heel violently against the rung of his chair.

The

horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act

a part, but, on the contrary, that it was impossible to avoid joining in.

Within thirty seconds any pretence was always unnecessary. A hideous ecstasy

of fear and vindictiveness, a desire to kill, to torture, to smash faces in

with a sledge-hammer, seemed to flow through the whole group of people like an

electric current, turning one even against one's will into a grimacing,

screaming lunatic. And yet the rage that one felt was an abstract, undirected

emotion which could be switched from one object to another like the flame of a

blowlamp.

La cosa orribile

dei Due Minuti d'Odio era che nessuno veniva obbligato a

recitare. Evitare di farsi coinvolgere era infatti impossibile.

Un'estasi orrenda, indotta da un misto di paura e di sordo

rancore, un desiderio di uccidere, di torturare, di spaccare

facce a martellate, sembrava attraversare come una corrente

elettrica tutte le persone lì raccolte, trasformando il singolo

individuo, anche contro la sua volontà, in un folle urlante, il

volto alterato da smorfie. E tuttavia, la rabbia che ognuno

provava costituiva un'emozione astratta, indiretta, che era

possibile spostare da un oggetto all'altro come una fiamma

ossidrica.

Thus, at one moment Winston's hatred was not turned against

Goldstein at all, but, on the contrary, against Big Brother, the Party, and

the Thought Police; and at such moments his heart went out to the lonely,

derided heretic on the screen, sole guardian of truth and sanity in a world of

lies. And yet the very next instant he was at one with the people about him,

and all that was said of Goldstein seemed to him to be true. At those moments

his secret loathing of Big Brother changed into adoration, and Big Brother

seemed to tower up, an invincible, fearless protector, standing like a rock

against the hordes of Asia, and Goldstein, in spite of his isolation, his

helplessness, and the doubt that hung about his very existence, seemed like

some sinister enchanter, capable by the mere power of his voice of wrecking

the structure of civilization.

It was even possible, at moments, to switch one's hatred this way or that by a

voluntary act. Suddenly, by the sort of violent effort with which one wrenches

one's head away from the pillow in a nightmare, Winston succeeded in

transferring his hatred from the face on the screen to the dark-haired girl

behind him. Vivid, beautiful hallucinations flashed through his mind. He would

flog her to death with a rubber truncheon. He would tie her naked to a stake

and shoot her full of arrows like Saint Sebastian. He would ravish her and cut

her throat at the moment of climax. Better than before, moreover, he realized why

it was that he hated her. He hated her because she was young and

pretty and sexless, because he wanted to go to bed with her and would never do

so, because round her sweet supple waist, which seemed to ask you to encircle

it with your arm, there was only the odious scarlet sash, aggressive symbol of

chastity.

The Hate rose to its climax. The voice of Goldstein had become an actual

sheep's bleat, and for an instant the face changed into that of a sheep. Then

the sheep-face melted into the figure of a Eurasian soldier who seemed to be

advancing, huge and terrible, his sub-machine gun roaring, and seeming to

spring out of the surface of the screen, so that some of the people in the

front row actually flinched backwards in their seats. But in the same moment,

drawing a deep sigh of relief from everybody, the hostile figure melted into

the face of Big Brother, black-haired, black-moustachio'd, full of power and

mysterious calm, and so vast that it almost filled up the screen. Nobody heard

what Big Brother was saying. It was merely a few words of encouragement, the

sort of words that are uttered in the din of battle, not distinguishable

individually but restoring confidence by the fact of being spoken. Then the

face of Big Brother faded away again, and instead the three slogans of the

Party stood out in bold capitals:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH

But the face of Big Brother seemed

to persist for several seconds on the screen, as though the impact that it had

made on everyone's eyeballs was too vivid to wear off immediately. The little

sandyhaired woman had flung herself forward over the back of the chair in

front of her. With a tremulous murmur that sounded like 'My Saviour!' she

extended her arms towards the screen. Then she buried her face in her hands.

It was apparent that she was uttering a prayer.

At this moment the entire group of people broke into a deep, slow, rhythmical

chant of 'B-B! ...B-B!' -- over and over again, very slowly, with a long pause

between the first 'B' and the second-a heavy, murmurous sound, somehow

curiously savage, in the background of which one seemed to hear the stamp of

naked feet and the throbbing of tom-toms. For perhaps as much as thirty

seconds they kept it up. It was a refrain that was often heard in moments of

overwhelming emotion. Partly it was a sort of hymn to the wisdom and majesty

of Big Brother, but still more it was an act of self-hypnosis, a deliberate

drowning of consciousness by means of rhythmic noise. Winston's entrails

seemed to grow cold. In the Two Minutes Hate he could not help sharing in the

general delirium, but this sub-human chanting of 'B-B! ...B-B!' always filled

him with horror. Of course he chanted with the rest: it was impossible to do

otherwise. To dissemble your feelings, to control your face, to do what

everyone else was doing, was an instinctive reaction. But there was a space of

a couple of seconds during which the expression of his eyes might conceivably

have betrayed him. And it was exactly at this moment that the significant

thing happened -- if, indeed, it did happen.

Momentarily he caught O'Brien's eye. O'Brien had stood up. He had taken off

his spectacles and was in the act of resettling them on his nose with his

characteristic gesture. But there was a fraction of a second when their eyes

met, and for as long as it took to happen Winston knew-yes, he knew!-that

O'Brien was thinking the same thing as himself. An unmistakable message had

passed. It was as though their two minds had opened and the thoughts were

flowing from one into the other through their eyes. 'I am with you,' O'Brien

seemed to be saying to him. 'I know precisely what you are feeling. I know all

about your contempt, your hatred, your disgust. But don't worry, I am on your

side!' And then the flash of intelligence was gone, and O'Brien's face was as

inscrutable as everybody else's.

That was all, and he was already uncertain whether it had happened. Such

incidents never had any sequel. All that they did was to keep alive in him the

belief, or hope, that others besides himself were the enemies of the Party.

Perhaps the rumours of vast underground conspiracies were true after all --

perhaps the Brotherhood really existed! It was impossible, in spite of the

endless arrests and confessions and executions, to be sure that the

Brotherhood was not simply a myth. Some days he believed in it, some days not.

There was no evidence, only fleeting glimpses that might mean anything or

nothing: snatches of overheard conversation, faint scribbles on lavatory walls

-- once, even, when two strangers met, a small movement of the hand which had

looked as though it might be a signal of recognition. It was all guesswork:

very likely he had imagined everything. He had gone back to his cubicle

without looking at O'Brien again. The idea of following up their momentary

contact hardly crossed his mind. It would have been inconceivably dangerous

even if he had known how to set about doing it. For a second, two seconds,

they had exchanged an equivocal glance, and that was the end of the story. But

even that was a memorable event, in the locked loneliness in which one had to

live.

Winston roused himself and sat up straighter. He let out a belch. The gin was

rising from his stomach.

His eyes re-focused on the page. He discovered that while he sat helplessly

musing he had also been writing, as though by automatic action. And it was no

longer the same cramped, awkward handwriting as before. His pen had slid

voluptuously over the smooth paper, printing in large neat capitals -

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER

over and over again, filling half a

page.

He could not help feeling a

twinge of panic. It was absurd, since the writing of those particular words

was not more dangerous than the initial act of opening the diary, but for a

moment he was tempted to tear out the spoiled pages and abandon the enterprise

altogether.

He did not do so, however, because he knew that it was useless. Whether he

wrote DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER, or whether he refrained from

writing it, made no difference. Whether he went on with the diary, or whether

he did not go on with it, made no difference. The Thought Police would get him

just the same. He had committed -- would still have committed, even if he had

never set pen to paper -- the essential crime that contained all others in

itself. Thoughtcrime, they called it. Thoughtcrime was not a thing that could

be concealed for ever. You might dodge successfully for a while, even for

years, but sooner or later they were bound to get you.

It was always at night -- the arrests invariably happened at night. The sudden

jerk out of sleep, the rough hand shaking your shoulder, the lights glaring in

your eyes, the ring of hard faces round the bed. In the vast majority of cases

there was no trial, no report of the arrest. People simply disappeared, always

during the night. Your name was removed from the registers, every record of

everything you had ever done was wiped out, your one-time existence was denied

and then forgotten. You were abolished, annihilated: vaporized was the

usual word.

For a moment he was seized by a kind of hysteria. He began writing in a

hurried untidy scrawl:

theyll shoot me i dont care

theyll shoot me in the back of the neck i dont care down with big brother

they always shoot you in the back of the neck i dont care down with big

brother --

He sat back in his chair, slightly

ashamed of himself, and laid down the pen. The next moment he started

violently. There was a knocking at the door.

Already! He sat as still as a mouse, in the futile hope that whoever it was

might go away after a single attempt. But no, the knocking was repeated. The

worst thing of all would be to delay. His heart was thumping like a drum, but

his face, from long habit, was probably expressionless. He got up and moved

heavily towards the door.

GO TO NEXT CHAPTER - 1984

www.mondopolitico.com/library/1984/1984_c2.htm

www.bookwolf.com/Free_Booknotes/1984_by_George_Orwell/Part_1_Chap1-1984/part_1_chap1-1984.html

Now I will tell you the answer to my question.

It is this.

The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are

not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power,

pure power. What pure power means you will understand presently. We are

different from the oligarchies of the past in that we know what we are doing.

All the others, even those who resembled ourselves, were cowards and

hypocrites. The German Nazis and the Russian Communists came very close to

us in their methods, but they never had the courage to recognize their own

motives. They pretended, perhaps they even believed, that they had seized

power unwillingly and for a limited time, and that just around the corner

there lay a paradise where human beings would be free and equal. We are not

like that. We know what no one ever seizes power with the intention of

relinquishing it. Power is not a means; it is an end. One does not establish

a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution

in order to establish the dictatorship.

The object of persecution is persecution.

The object of torture is torture.

The object of power is power. Now you begin to understand

me. ?

1984 - cap 3

ANALISI E RIASSUNTO

Se il Partito poteva ficcare le mani nel passato e dire

di questo o quell'avvenimento che non era mai accaduto

cio' non era forse temibile quanto la

tortura o la morte

?

...

E se tutti quanti accettavano la

menzogna imposta dal Partito

se tutti i documenti raccontavano la stessa favola

ecco che la menzogna diventava un fatto storico

quindi vera

.

In a way, the world-view of the Party imposed itself most

successfully on people incapable of understanding it.

They could be made to accept

the most flagrant violations of reality, because they never

fully grasped the enormity of what was demanded of them, and

were not sufficiently interested in public events to notice what

was happening. By lack of

understanding they remained sane.

They simply swallowed everything, and what they swallowed

did them no harm, because it left no residue behind, just as a

grain of corn will pass undigested through the body of a bird.

...

The essential act of war is destruction, not

necessarily of human lives, but of the products of human labour.

War is a way of shattering to pieces, or pouring into the

stratosphere, or sinking in the depths of the sea, materials

which might otherwise be used to make the masses too comfortable,

and hence, in the long run, too intelligent.

1984

***

Peter Davison , the editor of The

Complete Works of George Orwell, discusses its troubled genesis

and what might loosely be called "the autobiography Orwell never

wrote" - his Diaries and A Life in Letters -

now to be published for the first time in

the United States.

...

Two examples, both, fortunately, just

caught in time, might well illustrate the kind of errors

introduced by the printer. The title of Orwell’s last novel

appeared as:

Nineteen 48pt

Eighty-Four

’48pt’ was, of course, the type-size for the title-page. And

that famous formula, 2 + 2 = 5 appeared as 2r 29 5-

In the meantime I was asked to edit the extant manuscript of

Nineteen Eighty-Four –or 1984 as Orwell agreed it might be

titled in the USA. ...

And that is why, to this day, so

many of us ask, when facing some new challenge or outrage, ‘What

would George say?’

peter davison -

publishersweekly.com

- 2012

You realize what a

deterioration has happened inside your skull. At the start it is

impossible to get anything on to paper at all. Your mind turns

away to any conceivable subject rather than the one you are

trying to deal with, and even the physical act of writing is

unbearably irksome. Then, perhaps, you begin to be able to write

a little, but whatever you write, once it is set down on paper,

turns out to be stupid and obvious. You have also no command of

language, or rather you can think of nothing except flat,

obvious expression: a good, lively phrase never occurs to you.

richard eder - bostonglobe.com - 2012

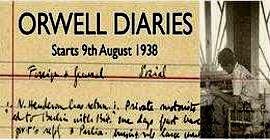

George Orwell diventa "blogger" dal 9 agosto 2008

-

theorwellprize.co.uk

Se fosse ancora vivo, probabilmente continuerebbe a pestare in piedi in

giro e a far polemiche magari usando anche il web come arma impropria. E

a oltre cinquant'anni dalla morte, George Orwell

torna a far sentire la sua voce e per la prima volta diventa

'blogger':

i suoi dia

ri

-

annotazioni personali, disegni, cronache politiche e letterarie -

saranno messi online dal 9 agosto su iniziativa dell'"Orwell Prize", un

premio dedicato alla scrittura politica consacrato alla memoria

dell'autore di "Animal Farm". Sul sito del premio, le pagine del testo e

anche un audio realizzato da un interprete d'eccezione: Peter Orwell,

figlio adottivo dello scrittore, che legge il diario del padre e lo

commenta.

ri

-

annotazioni personali, disegni, cronache politiche e letterarie -

saranno messi online dal 9 agosto su iniziativa dell'"Orwell Prize", un

premio dedicato alla scrittura politica consacrato alla memoria

dell'autore di "Animal Farm". Sul sito del premio, le pagine del testo e

anche un audio realizzato da un interprete d'eccezione: Peter Orwell,

figlio adottivo dello scrittore, che legge il diario del padre e lo

commenta.

apcom - parmaok.it - 2008

DIARIO E

BLOG POSTUMO

Si tratta di un'iniziativa dell'Orwell Prize – il premio letterario per

la scrittura politica dedicato all'autore britannico – che ha scelto

proprio la forma del diario elettronico per ridare voce a Orwell a più

di 50 anni dalla sua scomparsa. La data di apertura del blog non è

casuale. L'autore di «Animal Farm»(La fattoria degli animali) iniziò

infatti a tenere il suo diario (cartaceo, ovviamente) il 9 agosto del

1938, e da allora non smise mai di appuntare impressioni e pensieri,

nemmeno durante il ricovero presso il sanatorio del Gloucestershire in

cui trascorse otto mesi del 1949, un anno prima di morire.

alessandra carboni - corriere.it

these diaries reveal that the author of “Animal

Farm” was happiest cultivating his garden, observing the weather,

enjoying the beauty of spring flowers and watching over the health of

his hens. ...

Orwell is a saint of journalism, a major satirical novelist, a master of

the modern essay. Nonetheless, even the heartiest Orwell aficionado is

likely to find these diaries a letdown. Apart from perhaps 100 good

pages, they are repetitive, relatively trivial and surprisingly dull.

michael dirda - washingtonpost.com - facebook/orwell - 2012

...

In moments of crisis one is never

fighting against an external enemy

but always

against one’s own body

...

For the first time he perceived that

if you want to keep a secret

you must also hide it from yourself

...

Nothing was your own except the few

cubic centimetres inside your skull

...

For the first time he perceiv

We shall meet in the place where

there is no darkness

...

Siamo impegnati in un gioco in cui

non possiamo vincere

Alcuni fallimenti sono migliori di

altri

questo è tutto

1984

*

Torna alla luce un altro

PEZZo del puzzle della

vita di George Orwell

La prima moglie Eileen O’Shaughnessy

e’ sempre stata un’enigmatica figura e molto hanno discusso i biografici e i

critici sulla significativa influenza esercitata da lei sulle posizioni

ideologiche di Orwell.

lo scrittore DJ Taylor, considerato il maggior biografo e studioso di George

Orwell, ha scoperto un carteggio inedito della moglie che getta nuova luce sul

periodo cruciale della vita del romanziere britannico.

Le lettere

saranno pubblicate nel volume ‘’The Lost Orwell’’ .

sara’

possibile conoscere meglio quella che fino ad adesso era stata l’impenetrabile

relazione tra Orwell ed Eileen O’Shaughnessy che lo scrittore incontro’ nella

primavera del 1935 e sposo’ nell’estate del 1936 e che mori’ nove anni piu’

tardi durante un’operazione chirurgica.

adnkronos -

ilgiornale.it

- 2005

George

Orwell avrebbe tentato di violentare una amica d'infanzia Jacintha Buddicom

quando aveva 18 anni. Lo scrive la casa editrice Finlay nel libro "Eric and Us"

di cui da' notizia oggi il Sunday Times ... Secondo il libro Orwell si comporto' nello stesso modo con un'altra donna.

agr - corriere.it

- 2007

AMAZON CANCELLA I LIBRI DI

ORWELL

Accusata di usare gli stessi metodi di 'Big Brother' in 1984

Amazon cancella le edizioni elettroniche di '1984' e de 'La

fattoria degli animali' di George Orwell. Il reset e' avvenuto sia

dai lettori Kindle dei clienti che gia' avevano acquistato i film

che dalla piattaforma della societa' di e-commerce. In un dibattito

on line gli utenti paragonano l'azione di Amazon.com ai metodi di

'Big Brother' proprio in '1984'. L'azienda spiega che le opere erano

state pubblicate da un editore privo dei diritti di riproduzione.

ansa 2009

AMAZON CHIEDE SCUSA

"È stata una sciocchezza, abbiamo agito guidati

dal panico e senza pensare. Meritiamo tutte le critiche ci sono

piovute addosso ma cercheremo di fare tesoro di questa grave

disattenzione per giungere a conclusioni migliori in futuro".

giorgio pontico - punto-informatico.it - 2009

Amazon dovrà versare

un risarcimento di 150.000 dollari ad uno studente che l'aveva

citata per danni dopo la cancellazione senza preavviso delle copie

di "1984" di George Orwell dal suo eBook reader Kindle sul quale

aveva annotato degli appunti ...

redazione d.life - bitcity.it -

2009

Una rara copia della prima edizione di

1984

e' stata ritrovata

all'interno di un cassonetto con altri 200 volumi donati per

beneficenza all'associazione Lifeline a Wollongong, cittadina a sud

di Sydney, in Australia. Il libro dalla copertina rigida e' in

ottime condizioni, con una sovraccoperta rossa, che ne ha preservato

l'usura.

Si tratta di una delle 25.000 copie della prima edizione di ''1984''

stampata nel 1949... il raro esemplare e' stimato a oltre mille

dollari. ....

L'esemplare della prima edizione di ''1984'', romanzo in cui si

denuncia l'avvento di un 'grande fratello' totalitario, sara' messo

all'asta in Australia ....

libero-news.it - 2010

il personaggio immaginario creato da George Orwell nel suo celebre

libro "1984" sta avendo un nuovo successo commerciale alimentato

molto probabilmente dallo scandalo intercettazioni che coinvolge

l’intelligence americana come rivelato dallo scoop del quotidiano

britannico Guardian.

luisa de montis - giornale.it -

2013

George Orwell spiega 1984

In una lettera del 1944 contenuta nel

volume George Orwell: a life in letters

ripubblicato nel 2013 in inglese George Orwell spiega la teoria alla

base di 1984, il romanzo che avrebbe cominciato a scrivere tre anni

dopo e che sarebbe stato pubblicato nel 1949.

Nel testo Orwell mette in guardia contro la nascita di stati di

polizia totalitari che secondo lui stavano maturando.

Tutti i movimenti nazionali, dappertutto … sembrano assumere forme

non democratiche, raccogliersi intorno a dei führer superumani … e

adottare la teoria che il fine giustifichi i mezzi. Ovunque, la

direzione che il mondo sembra seguire è verso economie centralizzate

che possono essere fatte “funzionare” in senso economico ma che non

sono organizzate in modo democratico e tendono a stabilire un

sistema di caste. Accanto a questo si sviluppa … la tendenza a non

credere all’esistenza di una verità oggettiva, perché tutti i fatti

devono adattarsi alle parole e alle profezie di qualche führer

infallibile.

Orwell si dice anche preoccupato per l’indifferenza mostrata dai

cittadini verso la decadenza della democrazia, ma anche per le

posizioni assunte dagli intellettuali, spesso più vicine al

totalitarismo di quanto sembri.

“Penso, e l’ho fatto da quando è scoppiata la

guerra, nel 1936 o giù di lì, che la nostra causa sia migliore, ma

dobbiamo continuare a renderla tale, e questo comprende anche un

atteggiamento critico costante”.

internazionale.it - 2013

GEORGE ORWELL EXPLAINS IN A

REVEALING 1944 LETTER WHY HE’D WRITE 1984

I MUST SAY I BELIEVE, OR FEAR, THAT

TAKING THE WORLD AS A WHOLE THESE THINGS ARE ON THE INCREASE.

HITLER, NO DOUBT, WILL SOON DISAPPEAR, BUT ONLY AT THE EXPENSE OF

STRENGTHENING (A) STALIN, (B) THE ANGLO-AMERICAN MILLIONAIRES AND

(C) ALL SORTS OF PETTY FUHRERS OF THE TYPE OF DE GAULLE. ALL THE

NATIONAL MOVEMENTS EVERYWHERE, EVEN THOSE THAT ORIGINATE IN

RESISTANCE TO GERMAN DOMINATION, SEEM TO TAKE NON-DEMOCRATIC FORMS,

TO GROUP THEMSELVES ROUND SOME SUPERHUMAN FUHRER (HITLER, STALIN,

SALAZAR, FRANCO, GANDHI, DE VALERA ARE ALL VARYING EXAMPLES) AND TO

ADOPT THE THEORY THAT THE END JUSTIFIES THE MEANS. EVERYWHERE THE

WORLD MOVEMENT SEEMS TO BE IN THE DIRECTION OF CENTRALISED ECONOMIES

WHICH CAN BE MADE TO ‘WORK’ IN AN ECONOMIC SENSE BUT WHICH ARE NOT

DEMOCRATICALLY ORGANISED AND WHICH TEND TO ESTABLISH A CASTE SYSTEM.

WITH THIS GO THE HORRORS OF EMOTIONAL NATIONALISM AND A TENDENCY TO

DISBELIEVE IN THE EXISTENCE OF OBJECTIVE TRUTH BECAUSE ALL THE FACTS

HAVE TO FIT IN WITH THE WORDS AND PROPHECIES OF SOME INFALLIBLE

FUHRER. ALREADY HISTORY HAS IN A SENSE CEASED TO EXIST, IE. THERE IS

NO SUCH THING AS A HISTORY OF OUR OWN TIMES WHICH COULD BE

UNIVERSALLY ACCEPTED, AND THE EXACT SCIENCES ARE ENDANGERED AS SOON

AS MILITARY NECESSITY CEASES TO KEEP PEOPLE UP TO THE MARK. HITLER

CAN SAY THAT THE JEWS STARTED THE WAR, AND IF HE SURVIVES THAT WILL

BECOME OFFICIAL HISTORY. HE CAN’T SAY THAT TWO AND TWO ARE FIVE,

BECAUSE FOR THE PURPOSES OF, SAY, BALLISTICS THEY HAVE TO MAKE FOUR.

BUT IF THE SORT OF WORLD THAT I AM AFRAID OF ARRIVES, A WORLD OF TWO

OR THREE GREAT SUPERSTATES WHICH ARE UNABLE TO CONQUER ONE ANOTHER,

TWO AND TWO COULD BECOME FIVE IF THE FUHRER WISHED IT. THAT, SO FAR

AS I CAN SEE, IS THE DIRECTION IN WHICH WE ARE ACTUALLY MOVING,

THOUGH, OF COURSE, THE PROCESS IS REVERSIBLE.

AS TO THE COMPARATIVE IMMUNITY OF BRITAIN AND THE USA. WHATEVER THE

PACIFISTS ETC. MAY SAY, WE HAVE NOT GONE TOTALITARIAN YET AND THIS

IS A VERY HOPEFUL SYMPTOM. I BELIEVE VERY DEEPLY, AS I EXPLAINED IN

MY BOOK THE LION AND THE UNICORN, IN THE ENGLISH PEOPLE AND IN THEIR

CAPACITY TO CENTRALISE THEIR ECONOMY WITHOUT DESTROYING FREEDOM IN

DOING SO. BUT ONE MUST REMEMBER THAT BRITAIN AND THE USA HAVEN’T

BEEN REALLY TRIED, THEY HAVEN’T KNOWN DEFEAT OR SEVERE SUFFERING,

AND THERE ARE SOME BAD SYMPTOMS TO BALANCE THE GOOD ONES. TO BEGIN

WITH THERE IS THE GENERAL INDIFFERENCE TO THE DECAY OF DEMOCRACY. DO

YOU REALISE, FOR INSTANCE, THAT NO ONE IN ENGLAND UNDER 26 NOW HAS A

VOTE AND THAT SO FAR AS ONE CAN SEE THE GREAT MASS OF PEOPLE OF THAT

AGE DON’T GIVE A DAMN FOR THIS? SECONDLY THERE IS THE FACT THAT THE

INTELLECTUALS ARE MORE TOTALITARIAN IN OUTLOOK THAN THE COMMON

PEOPLE. ON THE WHOLE THE ENGLISH INTELLIGENTSIA HAVE OPPOSED HITLER,

BUT ONLY AT THE PRICE OF ACCEPTING STALIN. MOST OF THEM ARE

PERFECTLY READY FOR DICTATORIAL METHODS, SECRET POLICE, SYSTEMATIC

FALSIFICATION OF HISTORY ETC. SO LONG AS THEY FEEL THAT IT IS ON

‘OUR’ SIDE. INDEED THE STATEMENT THAT WE HAVEN’T A FASCIST MOVEMENT

IN ENGLAND LARGELY MEANS THAT THE YOUNG, AT THIS MOMENT, LOOK FOR

THEIR FUHRER ELSEWHERE. ONE CAN’T BE SURE THAT THAT WON’T CHANGE,

NOR CAN ONE BE SURE THAT THE COMMON PEOPLE WON’T THINK TEN YEARS

HENCE AS THE INTELLECTUALS DO NOW. I HOPE THEY WON’T, I EVEN TRUST

THEY WON’T, BUT IF SO IT WILL BE AT THE COST OF A STRUGGLE. IF ONE

SIMPLY PROCLAIMS THAT ALL IS FOR THE BEST AND DOESN’T POINT TO THE

SINISTER SYMPTOMS, ONE IS MERELY HELPING TO BRING TOTALITARIANISM

NEARER.

YOU ALSO ASK, IF I THINK THE WORLD TENDENCY IS TOWARDS FASCISM, WHY

DO I SUPPORT THE WAR. IT IS A CHOICE OF EVILS—I FANCY NEARLY EVERY

WAR IS THAT. I KNOW ENOUGH OF BRITISH IMPERIALISM NOT TO LIKE IT,

BUT I WOULD SUPPORT IT AGAINST NAZISM OR JAPANESE IMPERIALISM, AS

THE LESSER EVIL. SIMILARLY I WOULD SUPPORT THE USSR AGAINST GERMANY

BECAUSE I THINK THE USSR CANNOT ALTOGETHER ESCAPE ITS PAST AND

RETAINS ENOUGH OF THE ORIGINAL IDEAS OF THE REVOLUTION TO MAKE IT A

MORE HOPEFUL PHENOMENON THAN NAZI GERMANY. I THINK, AND HAVE THOUGHT

EVER SINCE THE WAR BEGAN, IN 1936 OR THEREABOUTS, THAT OUR CAUSE IS

THE BETTER, BUT WE HAVE TO KEEP ON MAKING IT THE BETTER, WHICH

INVOLVES CONSTANT CRITICISM.

YOURS SINCERELY,

GEO. ORWELL

openculture.com 2014 - fb/gorwell

2016

ORWELL SPIEGA PERCHE SCRISSE 1984 .PDF

Reality exists in the human mind and

nowhere else

1984 - prima pubblicazione 8.6.1949

https://auralcrave.com/1984-il-libro-che-uccise-george-orwell

.

ORWELL PATRIMONIO

unesco -

ha avuto un'influenza profonda sul pensiero umano

in tutto il mondo

archivi personali -

documenti - manoscritti - foto - autografi - consegnati nel 1960

all'university college london - diventeranno Memoria del mondo_Memory of

the World.

Il figlio adottivo Richard Blair, ha dichiarato: Questo prestigioso

riconoscimento conferito dall’Unesco agli Orwell Archives

dell’University College di Londra è una chiara indicazione del valore

attribuito alle opere dello scrittore .

redazione -

parlamentonews.it - panorama - 2018 -

ilpost.it/2024/08/20/george-orwell-archivio

- 2024

.

altri autori

home home

|

ri

-

annotazioni personali, disegni, cronache politiche e letterarie -

saranno messi online dal 9 agosto su iniziativa dell'"Orwell Prize", un

premio dedicato alla scrittura politica consacrato alla memoria

dell'autore di "Animal Farm". Sul sito del premio, le pagine del testo e

anche un audio realizzato da un interprete d'eccezione: Peter Orwell,

figlio adottivo dello scrittore, che legge il diario del padre e lo

commenta.

ri

-

annotazioni personali, disegni, cronache politiche e letterarie -

saranno messi online dal 9 agosto su iniziativa dell'"Orwell Prize", un

premio dedicato alla scrittura politica consacrato alla memoria

dell'autore di "Animal Farm". Sul sito del premio, le pagine del testo e

anche un audio realizzato da un interprete d'eccezione: Peter Orwell,

figlio adottivo dello scrittore, che legge il diario del padre e lo

commenta.